Pages

▼

Tuesday, April 23, 2019

Making a Muslin

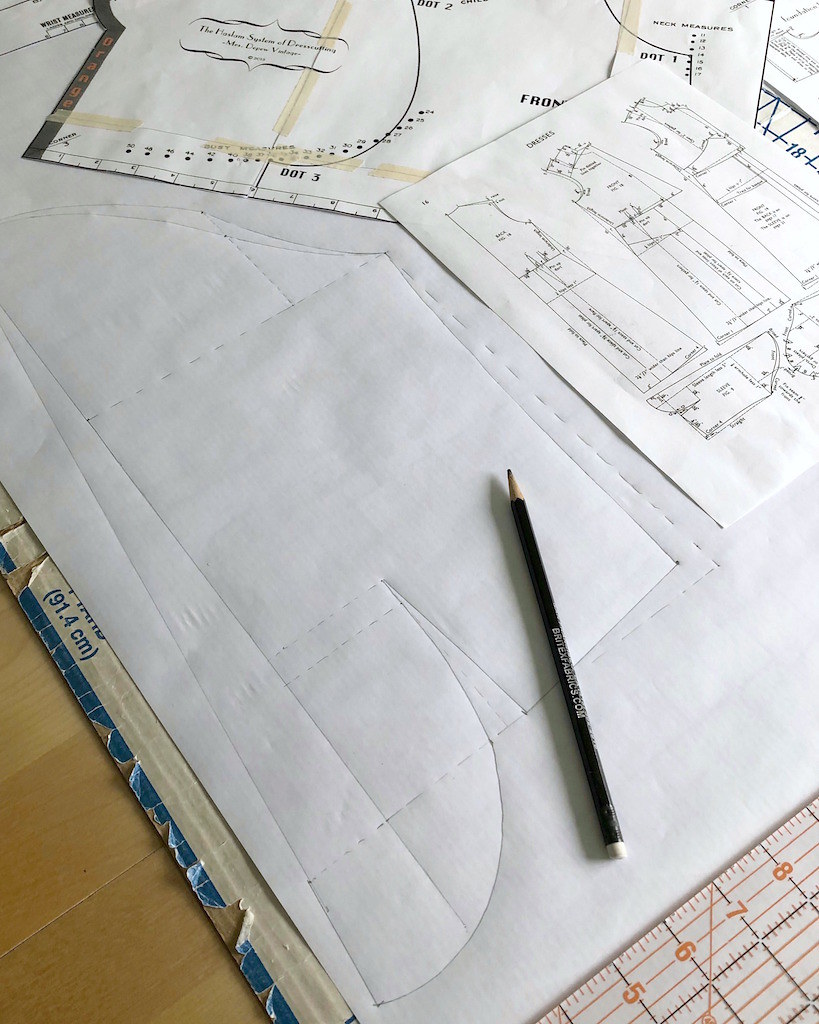

When we last left off with my Haslam System of Dresscutting project, I had drafted the pattern pieces in paper. I cleaned up those shapes and recut a new version of the pieces out of paper. Of course, these pieces have no seam allowances, which is the proper way to draft a garment. And since I was unsure what kind of ease was allowed with the Haslam draft, I wanted give myself a fair amount of seam allowance to play with.

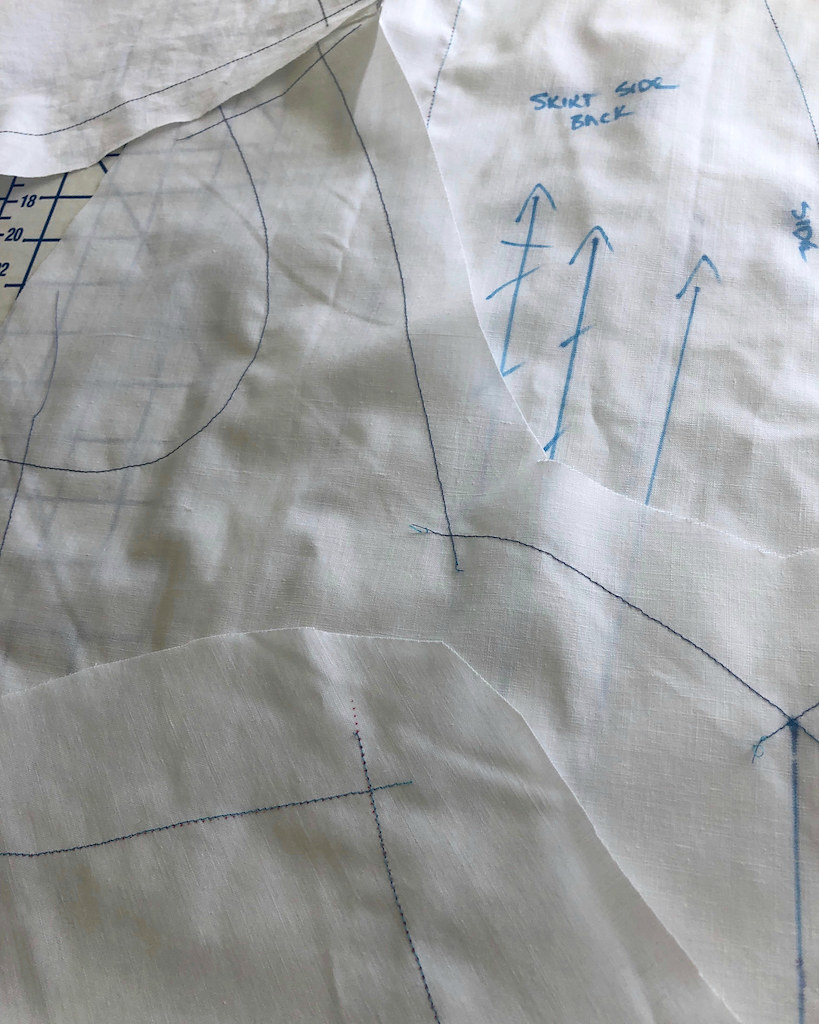

What I came up with was marking the stitching line (the outside of the paper pieces) with a tracing wheel and wax transfer paper on muslin. I then gave myself about one inch of seam allowance to play with around all of the edges, figuring that should be enough.

That was done with all of the pattern pieces.

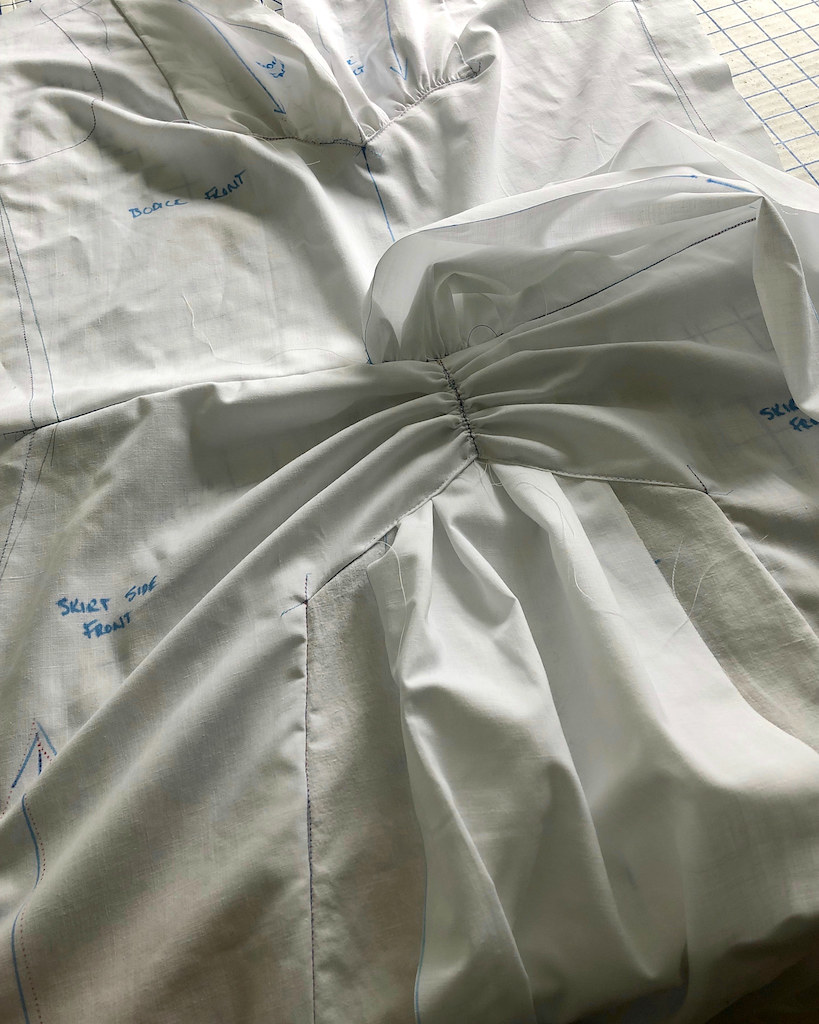

And then it was time to put everything together.

Since the instructions given with all Haslam patterns are extremely limited, I was pretty much on my own as far as construction goes. I ended up completing both the front and back as separate pieces, before stitching the shoulder and side seams together. I was inspired by this 1940s reproduction pattern, as a similar construction order is used.

My first time through I forgot about adding the front drape - which is another excellent reason to make a muslin, especially when there are no directions included!

I did cut the drape without any seam allowance so that I could see how I liked the proportions.

Next up, the sleeves!

I ended shortening the curve of the sleeve head in order get it to fit into the armscye properly. I made a second version of the sleeve to make sure I was happy with the result.

Surprisingly, the dress ended up rather large through the waist and hip area, but not the bust. I believe I removed almost two inches of ease in the waist, and probably a little more through the hips. This seems rather extreme, and while I cannot be certain it was not user error, I really think I did follow the diagrams correctly. I will have to remember this next time I draft one of these designs and see if I have a similar result.

Once I was happy with the fit, I trimmed my pieces so they had a 5/8" seam allowance. I will not be using an underlining, so I want a standard seam allowance to work with.

The only major alteration I needed to make (besides trimming excess ease through the waist and hip) was an erect back alteration, which is standard for me. Even using my actual measurements did not save me from this one! But I didn't have to add length to the torso, which is a first for me . . . except for that weird Cynthia Rowley pattern for Simplicity that was way too long, even for me. But I digress.

Up next is cutting into my fabric! And here she is, an Ellen Tracey brocade from Elliott Berman Textiles.

Monday, April 1, 2019

Drafting a Pattern from a Made to Measure Pattern Block

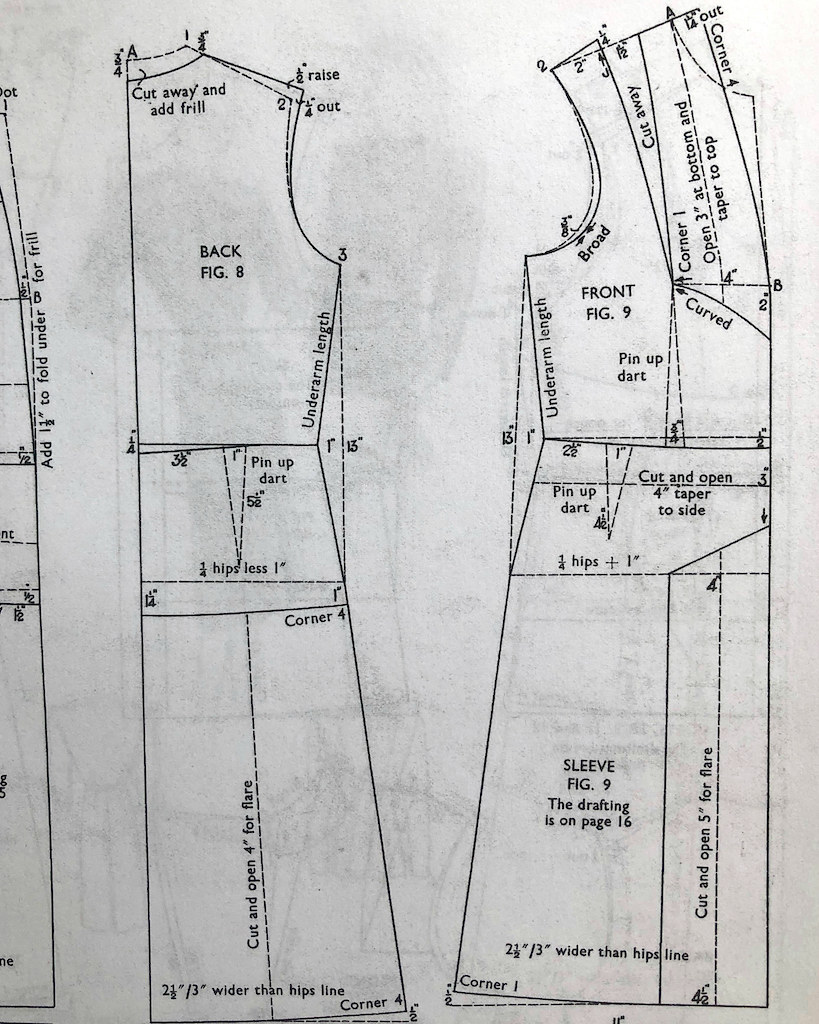

So the trick is now to turn these diagrams into . . .

pattern pieces that will make a dress that looks like the illustration. The Book of Draftings tells me that I am working with Figure 9, and that my draftings are to be found on pages 9 and 16. Great! The only other "Helpful hints for the making of garments given in this book" regarding Figure 9 is this:

The vest portion of this dress is gauged along the bottom and inserted. The front panel of the skirt is fixed in position and machined. Gauge the centre part above the panel into 3-in. space and draw to the figure. The drapery is slotted through and attached.

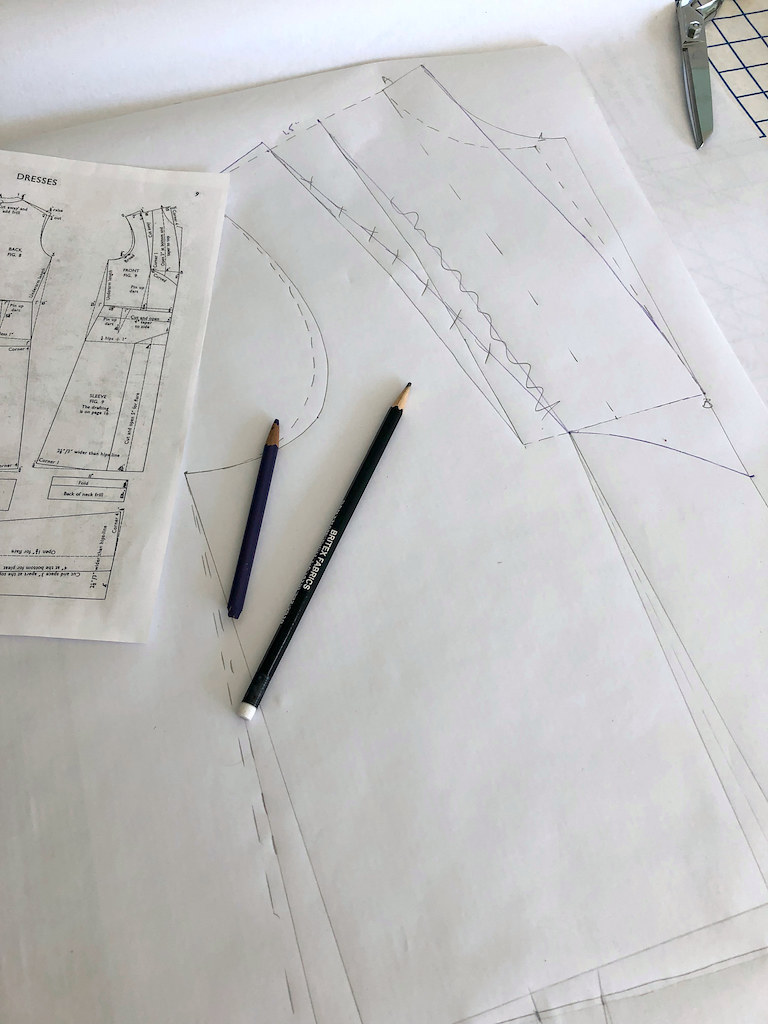

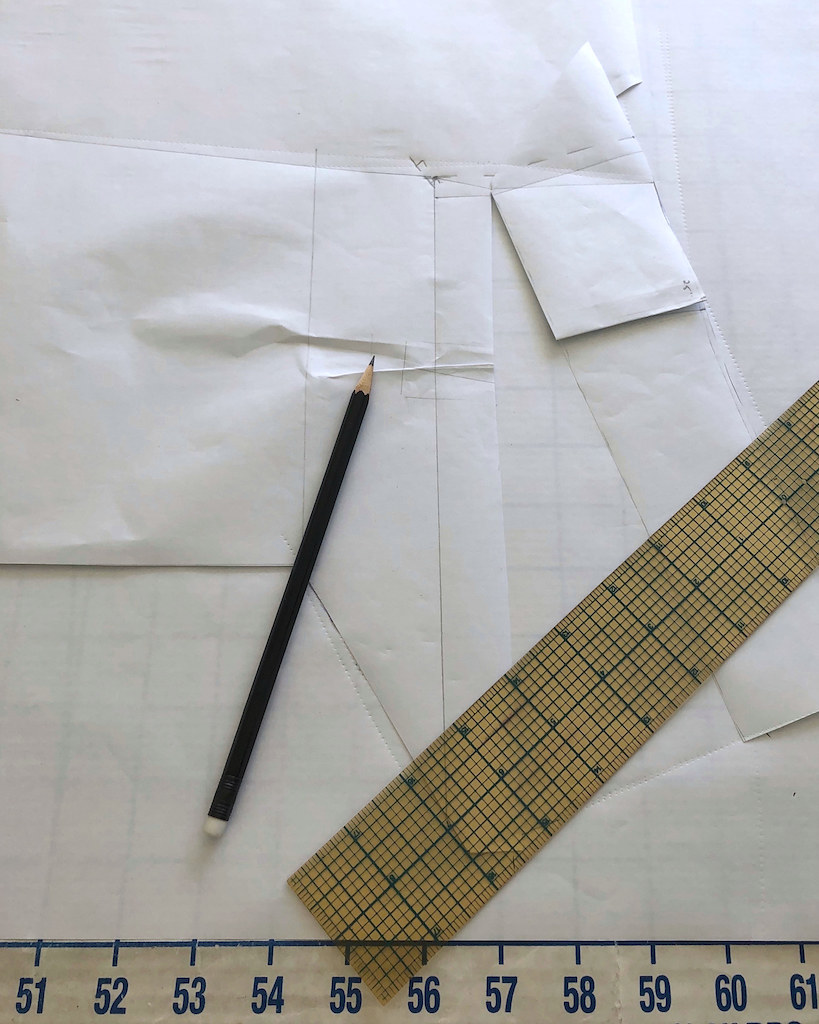

What I previously created is a basic block sketched in pencil on paper that should fit my body fairly well since is has been made using my specific measurements. What I now have to do is slice, dice, and manipulate the block into my Figure 9 diagrams to create a paper pattern for the dress.

I start with the back since there seems to be less to do there.

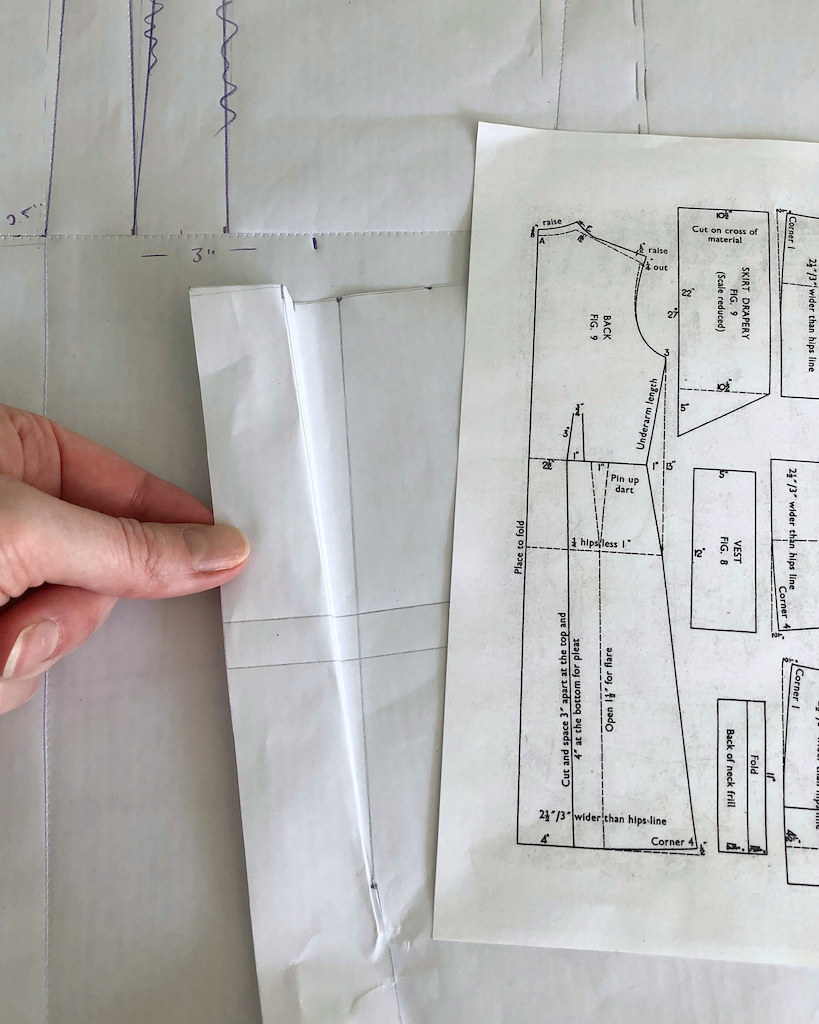

"Pin up dart" seems fairly straightforward, and to counteract that fold, I "open for flare" by slicing from the hem up to the point of the dart. That newly sliced and folded shape is then traced onto another piece of paper to give me my pattern piece. (In theory, at least!)

I decided to make a waist seam at front and back, although the illustration suggests that the back bodice and center portion of the skirt is one piece. But hey, I'm the one putting this thing together, so I am going to simplify where I can since this is my first attempt to make something using this new-to-me system.

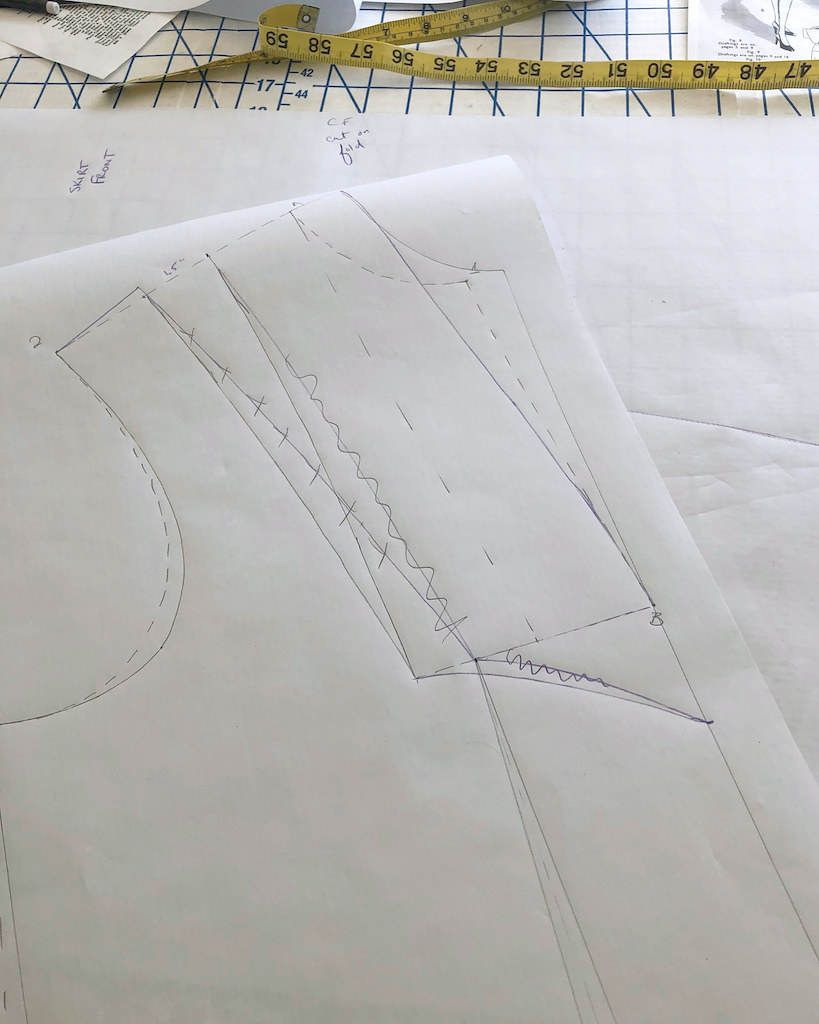

Now that I am a little more comfortable with the process, I decide to tackle the front. The first thing I do is cut out the center front inset for the skirt. The paper gets sliced from the hem to the angled section, and as suggested, is flared 5" at the hem, tapering to nothing at the top of the piece.

The skirt front is similarly sliced and flared to correspond to the diagram. This portion of the skirt is expanded, which will then be "gauged" at center front to created the gathered look of the illustration.

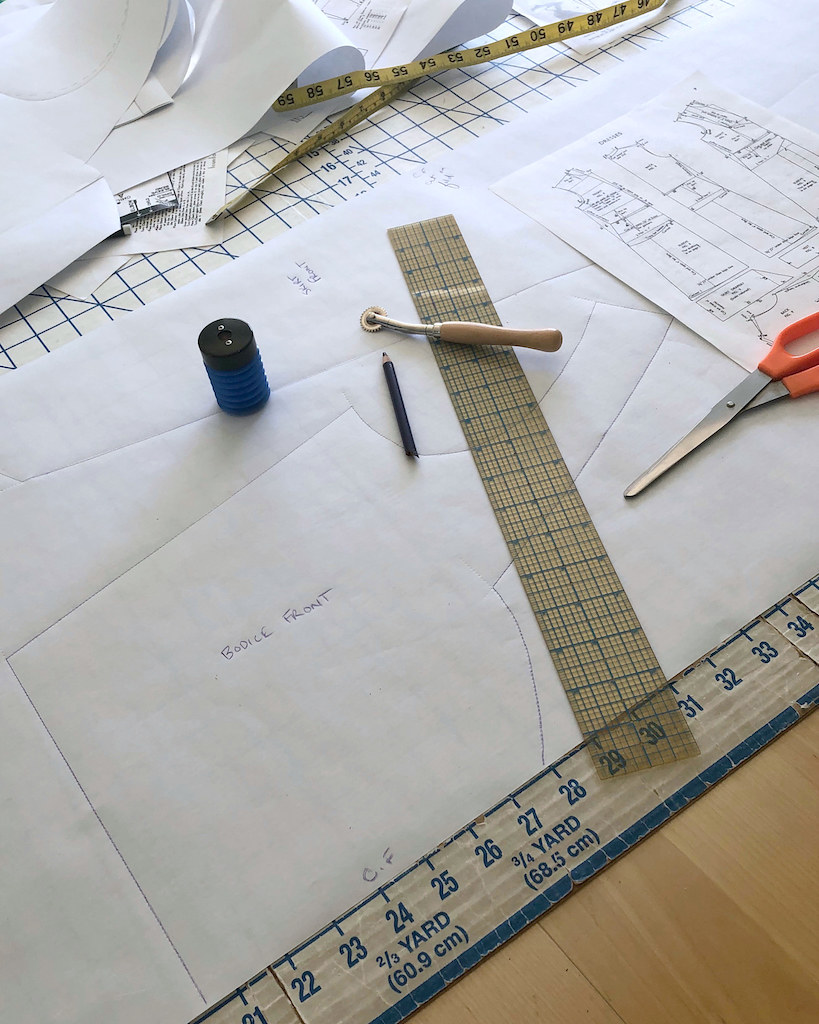

Moving on to the bodice front, you can see I made a few drafting errors. Thankfully, I caught my mistakes before moving on.

Remember, I am working without seam allowances of any kind. Those will be added in after all of the slicing and dicing is finished. This makes everything so much easier - especially when is comes to making sure corresponding pieces will fit together properly.

And eventually, I have my pattern pieces sketched out on paper.

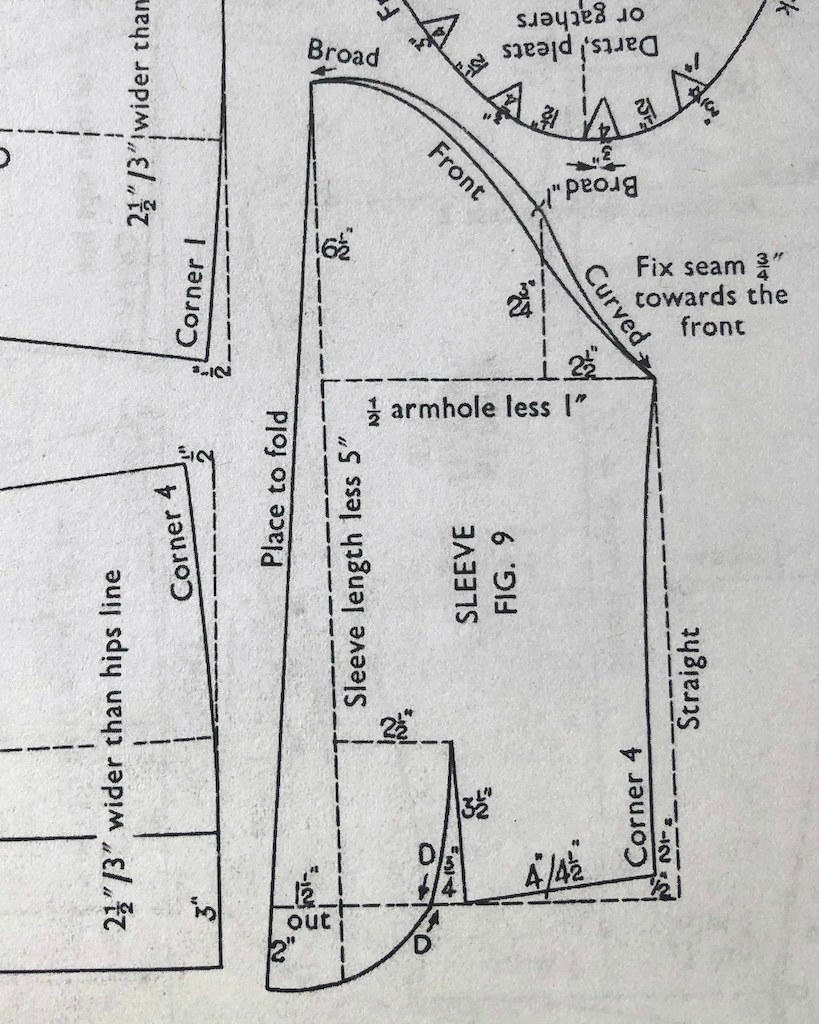

Since the sleeve is a one-piece sleeve and bears no resemblance to the two piece drafted sleeve in the foundation draftings, I really think that you are expected to draft this from scratch.

I am slightly confused how the measurements on such a diagram can be used for a system that allows for such a huge size variation. One assumes that a 24" busted individual's arm is going to be a whole lot different than an arm belonging to someone with a 50" bust. This also applies to the flared portions of the skirt and bodice pieces. If you want something to look gathered across a front portion of a chest that measures 12", adding 3" is significant, where that same 3" is going to do very little to gather fabric across 25".

I would be curious to know what size the original drafted illustrations were made for. There are specific designs made for children and some of the illustrations seem to suggest a more mature figure as they are drawn, so perhaps those issues are taken into account in some cases. But I think gathering and pleating suggestions might have to be tweaked if you want your garment to look exactly proportionate to the illustrated figures. But we will have to see how that goes . . .