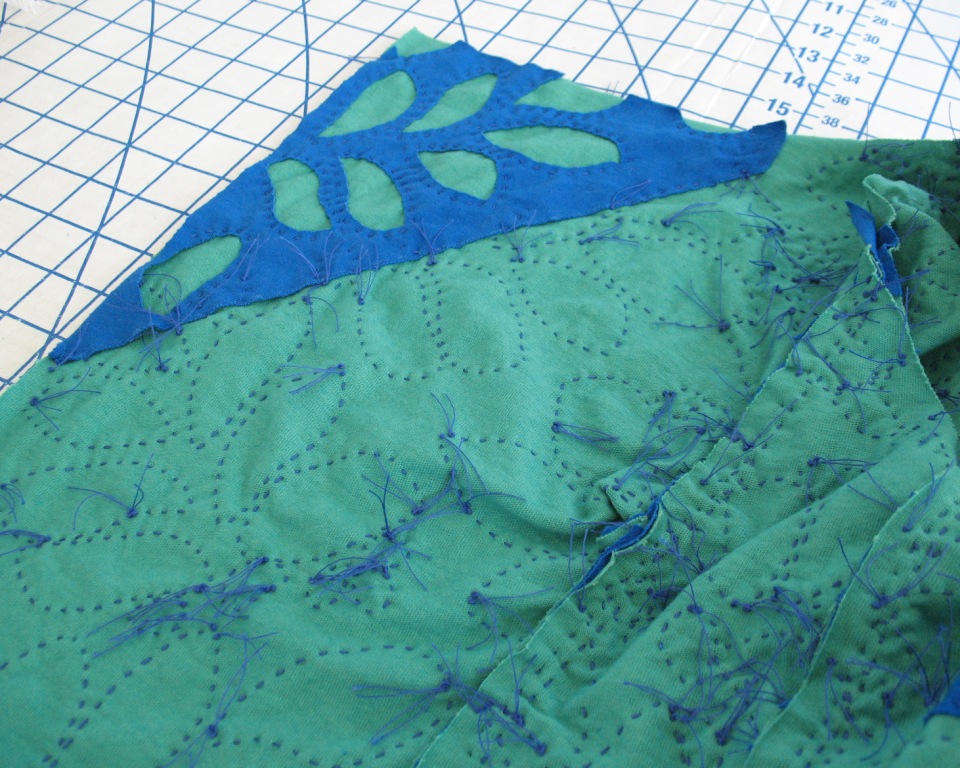

I am still working away on

my Alabama Chanin outfit. Most days, this is the project that I am drawn

to. I find hand sewing to be very

relaxing, and the cotton jersey seems to be extra kind to my fingertips. I have no needle wounds on the pads of my fingers,

even with daily sewing. The skirt is

finished, except for the waistband. I

did find a fold-over elastic that is a decent match to the sapphire blue cotton .

. . now I just have to decided if I want to replicate the waistband of

my first attempt, or go for the elastic.

I have also been contemplating Over-dressed: The Shockingly

High Cost of Cheap Fashion.

I confess, I had a hard time reading large chunks of this

book at a single sitting. Normally, I

devour books, but the subject matter was so disheartening to me, I could not manage

to read more than one chapter at a time.

I finished reading it weeks ago, but I have yet to return the book to

the library. I feel very unsettled, and keep

hoping to find some answer if I stare at the cover long enough.

What is clear is that ethical clothing made by workers

earning a living (not minimum) wage is expensive. Too expensive for anything except a niche

market, catering to those who not only have the funds, but appreciate the

effort and skill that goes into making them.

Throwing a designer name into the mix will certainly sell garments, but just

because a Dior or Chanel tag is stitched to the back of a skirt does not make

it haute couture, or even high quality. So

many consumers seem to be more interested in who they are wearing than what

they are wearing these days. What’s in a

name? I am much more interested in

quality. Which probably explains why I

enjoy making my own clothing.

So I thought I would play a game with myself and try to

figure out what this skirt I have made might actually cost in a shop . . . or

rather, what it should cost.

Alabama Chanin garments are sourced and made in the

United States,

are extremely labor intensive, the company compensates their artists with a

living wage, and seemed like an interesting choice for this exercise. I am also knocking off their skirt, so it was

a rather obvious place to start!

My skirt requires approximately 3 yards of

cotton,

dye, a

whole lot of heavy duty thread,

a stencil, and many, many hours of

labor. Alabama Chanin has fabric, a means of dying

their fabric so it is certainly more cost effective than their

$26/yard price tag, thread, stencils, and a method of spraying the design directly on cotton a

lot more efficiently than me.

I am not finding an exact match to my 31” long reverse appliquéd

skirt for sale, but similarly embellished pieces are available on their site from

$2,500 -

$3,000. That sounds like a lot

of money for a cotton skirt, right?!

If we say that a mid-length skirt will require approximately

three yards of

fabric and four

spools of thread, Alabama Chanin sells these

items for around $80. That cost

obviously factors in a profit, so I am going to guess the actual cost is around

$20 or $30. I am going to ignore the

cost of the

stencil. So, if we are

talking about a $2,000 garment, the supply cost seems rather negligible. Clearly, the main cost is the skilled labor

(as it should be!).

I started work on my skirt in early January. Dying the fabric took most of a day. Tracing my pattern pieces and cutting the fabric

also took a chunk of time. Making and

cutting my stencil also adds a few hours to the total. This process is obvious more streamlined for

a company that is set up for it – I started from scratch, and am at the beginning of the learning curve.

I was not keeping track of my sewing time, but for most of

January I spent at least one hour a day with a needle in hand for this project.

Some days I spent considerably more time, and some days

I had other things that took precedence and did not pick up the project at all. I also made a few test swatches for myself to

make sure I liked the result which added to my time.

So let’s call it forty hours, just for laughs.

In California (where I live), minimum wage is $9/hour. I am

confident a “living wage” in Alabama

is significantly higher than the mandated $7.25/hour minimum wage. If I more than double that number and pay

myself $15/hour for my 40 hours, that means I

would be paid $600 for the piece. Then, the $30 supply cost needs to be added. That brings the total up to $630

with no profit of any kind. If we multiply

by four, that gets us to $2,520 – right around the cost of an original Alabama

Chanin skirt.

Most people would never dream of paying $2,000 for a cotton

skirt, even if they could afford it. But

once you have created a well made or highly embellished garment that takes

thirty or forty hours to produce, that number begins to sound reasonable.

Much of this process, of course, would be more time

efficient in the Alabama Chanin Factory.

I wish I knew how quickly one of the real Alabama Chanin skirts are

stitched together. But I simply cannot

imagine that from start to finish, the highly embellished versions could take

less than twenty or thirty hours of time.

I am not at all familiar with the way MSRP is

calculated. However, I am very familiar

with the sale price insanity that pervades the U.S. retail industry, which so many of us have come to expect. Every day I receive email notices of 25, 30,

sometimes even 50% off retail prices. With

all of those 50% off sales, it is not hard to believe that manufacturers are

selling their wares at four times the rate of cost to the manufacturer, or a

200% markup on top of the manufacturing costs.

I think (or like to think) that Alabama Chanin is paying more to their

skilled workers, and using less of a mark-up, but I have no way of knowing

that.

Personally, I do not consider my time when I make clothing for

myself. I love the process as a creative

outlet, and can’t image not sewing. To me, the "cost" of one of my hand made dresses is the money I spend on patterns, fabric, and notions. But I would most certainly expect to be

compensated for my time if I was to sell one of them.

Most of my new wardrobe pieces are hand-made, and have been

for quite a few years now. It has made

me re-evaluate the retail world. Last

year I purchased two Old Navy cotton cardigan sweaters. The price was low, but I cannot

imagine how low the cost of labor must be in order to sell a garment for so

little money. It boggles my mind.

I know this topic has been discussed ad nauseam. Unfortunately, the demand for more and more

clothing reflecting the latest trends each and every week means companies have an incentive to continue to produce fast fashion.

I doubt the seamstresses and tailors working on those

glorious Worth gowns from the turn of the century were making good wages, but

instead of fifty t-shirts, they were toiling over a single gown. That is no longer feasible (and never was for the majority of the population to fill their closets). Where can we find a balance?

What would you pay yourself as an hourly wage for your hand work to feel sufficiently compensated? What do you think is reasonable for a consumer to expect to pay?

It is upsetting that so very few artisans are paid according

to their talent and skills. Will this ever change? I have to wonder what the men and women in the haute couture ateliers are currently paid.

I am not really sure where I am going with this, but I just

had to spell it out for myself.

And as cliché as it sounds, they certainly don’t make things like they used to. But I can, and will!

[This post is just a theoretical exercise. I have no way of confirming any of my

assumptions, other than the prices listed on the Alabama Chanin website and

using a search engine to find out the minimum wage in Alabama.

I also think Natalie Chanin understands the fact that many people will

never be able to afford her pieces, and I appreciate the fact that she has shared so much of

her process through her books and classes.]